King County: I’m off on another long distance bike tour. This time, across the United States and with a companion. Sean, my fiancé. The tour officially started last Friday on a brilliantly sunny day in Wallingford, one of Seattle’s many charming urban villages. We spent the prior afternoon clearing the last of our things out of our apartment and made final decisions about the items we were willing to pedal over mountains passes and across endless, windy stretches of road. All seemed to be going well with our packing until I discovered the condiments.

There were so many. We had two fish sauces, two sticky bottles of Trader Joe’s Soyaki Teriyaki Sauce, jams, horseradish, several kinds of mustard, and innumerable bottles of hot sauce. Condiments are a sign of stability; they accumulate when you stay in one place. I had mostly been positive and calm during the preceding days of packing, moving, wrapping work projects up, and goodbyes, but the condiments seemed to paralyze me. The sleepless nights spent thinking about packing details and last minute to-dos caught up with me as I stared blankly into the fridge and started to cry. Fortunately, crying quickly turned to laughter thanks to the arrival of our good friend Mary who came to help with the final move-out push. “Just give us the condiments and we’ll decide which ones to keep,” she assured me as we threw the last few bottles into a cardboard box. Mary and Mike have way too many hot sauces now, but condiments do not travel well.

….

My bike felt obese when I first got on it the next morning.

We biked past my favorite, overpriced coffee shop under the Aurora Bridge, past the marina that was my second home the summer of ‘10, and over the sparkling Ship Canal on the Fremont Bridge where Seattle’s first bike counter displayed a 4 digit number. The weather was perfect. Why did it have to be so damn beautiful the day we left? I felt like Seattle had put on her lipstick and most flattering outfit in one final attempt to show me that I was making the wrong decision to leave. But, it was too late. The condiments were gone. The boxes stored.

….

Waiting for the ferry, I looked at all the buildings. I spent thousands of hours in the office building on 1st and Spring–some hours stressful, some exhilarating, and many just ordinary. In other buildings, I remember tense meetings, giving presentations, speaking up, and quietly taking notes. I remember sitting in lobbies of other buildings silently rehearsing answers to possible interview questions when I was job-searching after college. There was my dad’s building. When I was a kid my mom and I would drive in the blue station wagon to 4th and Madison and pick him up when he missed the last bus. I loved the time alone in the car with my mom listening to Oldies together.

The ferry arrives, we ride on, and the Seattle skyline gets smaller and smaller.

Kitsap County: After a short ferry ride and just 20 minutes of biking the city already feels far away. We turn up the road to Aaron and Dana’s farm and I see Dana weeding a row of spring greens. She is wearing overalls and a big farmer hat. She looks beautiful, strong, and healthy. Her freckles are already out in full force and it is just May. We hug and she tells me she is pregnant. I tell her congratulations and she tells me she feels like throwing up all the time. She tells me about how it feels to have morning sickness. Sean nods politely and I think about when I told Dana what “having a period” meant almost two decades ago when we were tomboys playing in the woods together. We keep the visit short, but I close my eyes tight when I hug her goodbye.

Jefferson County: Crossing the Hood Canal Bridge isn’t as scary as I expect. In fact, it isn’t scary at all. Relief.

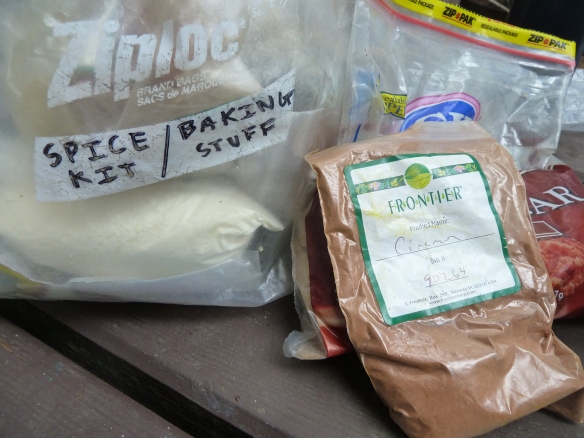

We decide to camp at Oak Bay State Park. The campsite is on an isthmus and there are men in rubber boots digging for clams on the beach, but no other campers. I didn’t even know this place existed, but I really like it. I make vegetarian corn dogs for dinner with the cornmeal, flour, and Field Roasts we brought. Sean is in awe, but we both agree that a condiment would be nice.

We go to Port Townsend the next morning. The bike path into town is separated from the road and in the shade. Perfect. The town seems to be celebrating the weekend sun. We go to the Farmer’s Market, sit at a picnic table where a corgi is leashed, and eat an entire round of Mt. Townsend Creamery cheese with rolls. We don’t talk. We just look at the scene: street musicians, kids chasing each other, busy cooks at food carts, friends laying on the grass talking.

Island County: After we get enough of the Farmer’s Market, we take another ferry to Whidbey Island and the views are stunning. There are farms on rolling hills with the Olympic Mountains in the background. Part of the ride is on the Kettle Trails, another separated bike path–but then we approach Oak Harbor and not only does the path disappear, so does the shoulder. We eventually realize that we should have turned a few miles back to stay on the suggested bike route, but we don’t really have the energy to bike back up the steep hill into town, so we push forward on the busy road. Fortunately, the shoulder reappears a few miles out of town–but the last 19 miles of our ride is loud and somewhat stressful with a steady stream of cars and trucks passing us.

When we arrive at Deception Pass State Park, there is a long line of cars waiting to get into the park. Everyone is trying to enjoy the first sunny Saturday of the season. The overwhelmed park ranger informs that car ahead of us that all the campsites are full, but we stay in line to inquire about the hiker/biker campsites. Most Washington State Parks reserve campsites for campers arriving via human power–and we are in luck. There are open campsites for bikers. The park is teeming with people, but it is a beautiful night and after dinner we sit on the beach in the evening sun for almost an hour. When we get back to our tent, a friendly trio of British grad students bike touring from Vancouver to Mexico is at the campsite next to us.

Skagit County: After crossing the Deception Pass Bridge the next morning, and rallying to celebrate a Northwest version of Cinco de Mayo, we buy guacamole ingredients at a roadside fruit and vegetable stand. I make a delicious guacamole at Bay State Park on Padilla Bay while Sean unsuccessfully retraced several miles of our ride looking for his Crocs.

On Tuesday we wake up in the morning and I say goodbye to the ocean and the smell of salt water. I will miss that smell. We head east and spend most of the day on the old Skagit Highway–going past working and dilapidated farms. By mid-afternoon it is almost 90 degrees and I am exhausted. We stop at Chom’s Mini-Mart in Marblemount and buy provisions to help fuel our ride over the North Cascades. The selection is slim, but it’s the last store for almost 80 miles and we’ll burn a lot of calories the next day. After we pay, I ask the attendant if it would be possible to fill up our water bottles and without taking his eyes off the blaring TV screen, all he says is, “bathroom.”

I perk up after drinking some water and eating peanut butter M&Ms. We bike 15 more miles to Newhalem where we camp along the Skagit River for the night.

Whatcom County: The next morning we prepare to climb three mountain passes in order to get over the Cascades to the Methow Valley. It’s a Tuesday and the traffic on Highway 20 is very light. We go for 10 to 15 minutes at a time without any traffic passing. The day heats up quickly, but the mountain snow is melting quickly at this time of year and there are alpine streams at regular intervals providing shots of cool air, mist, and water. We pedal, drink water, stop occasionally for snacks and sunscreen–and pedal more. We get into a rhythm and eventually we gain enough elevation that there is snow on the sides of the road. As my head starts to get fuzzy from the heat, exertion, and repetition a car drives by and gives us a thumbs up and fist pumps out the sunroof. This small gesture seems to give me a boost.

Okanogan County: In total, we do about 7,000 feet of climbing by the time we get to the third and final pass of the day–Washington Pass–at close to 6 PM. The descent into the valley is long and I have a smile plastered on my face. I wear a down jacket and although I can feel the temperature increase as we descend there are still pockets of incredibly cold air from the icy streams feeding into the Methow River. Although we have a cabin to stay in just 40 miles away, there is no way we can bike anymore and so we set-up camp at the bottom of the Pass. We eat a huge dinner and relax. We’re surrounded by jagged mountains that are pink and orange. Then, as the sun sets, the pinks and oranges disappear and the mountains become muted colors of gray, black and white. While biking into Winthrop the next morning, an old man yells at us, “Looks like you two are the first cross-countriers of the year!”